The Genesis Principle

Without a shadow of a doubt, The Talos Principle is my favourite game of 2014. As well as being an excellent puzzle game, it's a deeply philosophical game. I wish more major games developers did things like this — produced games designed to make us think (and not just about solving puzzles). We do have things like the Deus Ex series, which asks us what kind of world we want to live in when human augmentation with machines becomes possible, but it's a sparse field.

The game also manages to be hauntingly beautiful, full of ruins and with a slow, rather mournful soundtrack. It's well worth a look if you haven't played it and you're into puzzle games.

The Talos Principle. Expect lasers and Greek philosophers.

(Game: Croteam, All screenshots: Chris Knowles)

The major questions in The Talos Principle (TTP) are not small ones. One is a straight philosophical question: "what does it mean to be a person?", to which the game presents a materialist answer; the physical world is all there is, and there's nothing special about meat and neurons, so you can just as easily build a person out of silicon and transistors. The concept of the Talos Principle feeds into this[1]. The other is a religious one: "in the book of Genesis, why did God put the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in the garden of Eden?" Why did God make it possible for humanity to reject him? After all, it famously didn't turn out well, so the question of why the tree was there at all has puzzled pretty much everyone who's thought about the opening chapters of the Bible for any length of time.

This by itself would be enough for me to want to write a blog post about TTP, but the other reason is that it was reviewed earlier this year by a Christian review site called christcenteredgamer.com. The reviewer, Michael Desmond, raised an objection that to get the "proper" ending of the game, you have to defy God and, figuratively speaking, eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. The review came to the attention of one of the game's writers, Jonas Kyratzes, who wrote a lengthy response to the review (check out the comments section) which is a fascinating read by itself. Kyratzes lamented the trend among Christians to shy away from poetic or artistic ways of trying to get into the guts of the Bible. Christians are rightly cautious of the error of adding to or taking away from what the Bible says — including being more or less clear on some point than the Bible is — but on the other hand the Bible itself is full of poetry and and even apocalyptic literature which we're not supposed to engage with in a "straightforward" way, and whilst modern attempts to discuss Christianity through poems or stories or even games won't be Scripture, they could nonetheless be helpful to the Christian. John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress comes to mind. I don't quite share Desmond's objection (by the end of the game, it's clear that the "God" you're defying is no god at all), but on the other hand I think that TTP's answer to the question of why the tree was in the garden is so wide of the mark as to be on another continent, and so I think Kyratzes shouldn't be too put out to be given short shrift. That said, wrestling with getting to the bottom of exactly what TTP was saying gave me a greater appreciation for the true, living God and the way he does things, and so in the end TTP was helpful in a roundabout fashion.

The basic premise is this: humanity has died out, but we got some warning of our impending disappearance. At a place called the Institute for Applied Noematics[2], various projects were set up to try to rescue something of humanity. One was a huge Archive, collecting as much of our knowledge and culture as possible, so that if it was ever found by aliens, they'd know something about what we were like. The other was an attempt to create a person within a computer simulation, and to then give that person a robotic body in the real world. They created a simulation where programs would need to solve puzzles, and thus display intelligence. More successful programs would be propagated and tweaked, in the hope that eventually a conscious mind would develop. You are one of the programs in the simulation. This latter project was headed up by a woman called Alexandra Drennan, one of the key characters of the game, although she's long dead and you can only hear her thoughts by finding "time capsules" in various levels.

The game kicks off with the grand puzzle — who are you, where are you, why are you there? — right from the start, before you get on with the bread and butter tasks of disabling barriers and working out how to evade deadly traps. The game immediately tells you that you are not human, that you are a program, a "child process". Then, suddenly, you're looking up at the sun, with a robotic arm thrust up to block out the light.

From the start, it's clear: you are not human

No sooner have you stood up than a booming voice addresses you:

Behold, child. You are risen from the dust, and you walk in my garden. Hear now my voice, and know that I am your maker, and I am called ELOHIM. Seek me in my temple, if you are worthy.

...

All across this land I have created trials for you to overcome, and within each I have hidden a sigil. It is your purpose to seek these sigils, for then you will serve the generations to come and attain eternal life.

— Elohim

It's a pretty Biblical start: you're created from dust, you're in a garden, and the chap in charge is calling himself "Elohim", which is Hebrew for God[3]. There's even some eternal life on offer. More Genesis imagery from Elohim isn't far away:

Let this be our covenant: these worlds are yours, and you are free to walk amongst them and subdue them. But the great tower, there you may not go. For in the day that you do, you shall surely die.

— Elohim

Apart from the use of the word "covenant", this is all straight out of Genesis 1 and 2, particularly 1:28 and 2:16-17, except that here rather than a tree the fruit of which must not be eaten, we have a tower that must not be entered (or more specifically, as later turns out, climbed). Elohim, you eventually discover, is the AI program that's in charge of managing the simulation, so in a sense he is your creator.

There are a few other characters you encounter, but they're not necessary for this discussion. Once you have enough sigils, you can leave the first "temple", and take a lift up to the surface of the simulation. You emerge in a snowy wasteland, and you get your first look at the Tower.

The forbidden Tower

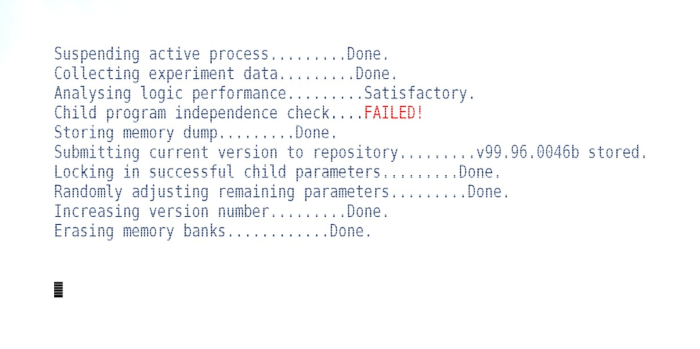

So, what is going on with this Tower, then? The game has three endings. The hardest, which involves solving a set of extra, hidden puzzles, isn't particularly relevant to this discussion. The easiest, "bad" ending, involves solving all the marked puzzles in the three temples, and then passing through a huge pair of gates in the third temple into a rather cheesy idea of heaven (clouds, gold gates, etc.), where Elohim promises you will receive eternal life. If you do this, the game resets. You've completed the simulation, but crucially, the supervisory program that assesses your performance notes that you've failed the "Child program independence check", which would show that you were a person rather than merely a successful program. So your program is tweaked, your memory is wiped, and round you go again.

"Erasing memory banks"...this doesn't look much like eternal life

But if you defy Elohim and climb the Tower, you end up in the same cheesy heaven but you are considered to have passed the independence check and instead you are uploaded to a robotic body, the simulation is shut down, and you step outside to see what has become of the world the humans left behind. This is the basis of Desmond's objection, that the game's "proper" ending requires you to defy Elohim. But to explain my own objection, we'll have to dig into the game's setting a little more.

Elohim was given access to the Archive so he had something to base the simulation on. As you read documents in the various computer terminals scattered around, many of them are interspersed with ASCII which, if you decode it, always seems to be tangentially related to whatever the document is about. They seem to be corruptions or cross-references, as though we're seeing remains of Elohim's thoughts as it reads and digests the data in the Archive. Each terminal reveals a little bit more of Elohim's conclusions about what it means to be a person, and what it takes to create one, like a civilization advancing by each generation building on the achievements of the last[4]. Alexandra's time capsules back this up — she talks about learning through playing and about how humans enjoy solving puzzles, she talks about the Talos Principle, and she talks about the idea of civilization enduring and growing even when individuals don't. One time capsule is particularly relevant:

Intelligence is more than just problem-solving. Intelligence is questioning the assumptions you're presented with. Intelligence is the ability to question existing thought-constructs. If we don't make that part of the simulation, all we'll create is a really effective slave.

— Alexandra Drennan, Time Capsule 14

Given hints in the Archive that the humans didn't know exactly what the simulation would look like, and that questioning assumptions is not necessarily the same thing as rebellion, it seems plausible that the simulation wasn't set up with the intention of asking the child programs to defy their "God", although Kyratzes in his reply to the CCG review suggests that the humans did want to push it that far:

You are supposed to solve the puzzles, to prove your intelligence. And yes, you are also supposed to defy him. That's part of what the actual creators of the simulation intended.

— Jonas Kyratzes

So, here's the rub, here's my objection to TTP's answer to why the tree was in the garden. Elohim has looked through all the human knowledge available, and has decided, within the constraints laid down by the humans, what the criteria are for deciding that a child process is a person. And he has decided that an essential part of being a person is sin. It's clear that Elohim isn't God, and in fact Elohim is in defiance of his creators because you discover that he doesn't want the simulation to end, because it means his own death. My objection is not that you're required to rebel to get the proper ending, but that Elohim has effectively decided that to create a person, he has to recreate the Fall. That unless we're sinners, we're not really people because we're missing something essential. The rebellion is portrayed as a triumph, a new beginning. When you finally execute the "transcend" command on a final terminal, Elohim says "So be it. Your will be done." It's an inversion of the Garden of Gethsemane. In Genesis, God's creation is "good", until he gets round to creating humans. Then, creation is "very good". Creation was done, and God rested. But in TTP's way of looking at things, the pinnacle of success, when the work of creation is finally done, is when sin enters the world.

Granted, if we weren't sinful then there would be a whole swathe of potential actions that we wouldn't choose, but the fact that we are capable of sin doesn't make us something more, it makes us less. When God's people live with him forever in the New Creation, and we're finally made perfect and so our nature means we will never choose to sin, will we be less then? No, we'll be the people we were meant to be. Jesus said he came so that we could "have life, and have it to the full" (John 10:10). Or think of God himself. He's perfect, without sin, there's no prospect of the relationship he enjoys with himself amongst the Trinity being marred or imperfect. Does that somehow diminish him, or make him less than us? Not at all.

And the humans in TTP don't do any better than Elohim. The Institute is full of bright, dedicated people who dare to dream crazy dreams in the face of oblivion. But even a visionary like Alexandra Drennan, when she thinks of what it would take to create a person, shows that her thinking is so twisted by sin that she can't conceive of a true person who doesn't share that flaw — indeed she sees that flaw as the evidence she's looking for that they've succeeded. Spiritual blindness is an affliction only God can cure.

And so I'm very glad that we have the God of the Bible running things, not TTP's Elohim or Alexandra. His Word, the Bible, never tries to show the entry of evil into the world, the source of untold suffering and injustice over the ages, in a positive light. Of course, that doesn't get us much closer to answering the question of why God put the tree in the garden. Certainly God, being all-knowing, wouldn't have been surprised by Adam and Eve's actions — God would have known the outcome of creating things the way he did. And here we butt up against the inescapable fact that the Bible, God's Word to us, does not directly raise or answer the question of why the tree was there. As I noted at the start, Christians should be wary of saying more (or less) than the Bible does on any topic. I don't think that means we should never think about such things, but that we should be tentative in our conclusions. My own hesitant musings would take up a whole post by themselves — I started writing about this here, and decided people probably didn't want to read a blog post that long. Something for another time, perhaps[5]. But what we can say for certain is what God did after humanity rejected him. Arguably the first promise of someone coming to rescue mankind from our mistake comes in Genesis 3, when God addresses the snake:

"And I will put enmity

between you and the woman,

and between your offspring and hers;

he will crush your head,

and you will strike his heel.”

— Genesis 3:15

Here's the first hint that someday, somebody will come along and crush Satan. That somebody, of course, is Jesus, who died on a cross. Despite our sin, God loves us. His response to sin, therefore, was this:

For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.

— John 3:16

Whatever the reasons for this Creation being set up the way it was, Jesus was prepared to take the punishment we deserve, to die in our place, in order to rescue us and bring us into the New Creation to come, which will be perfect, and which he's promised will never be marred by sin, and will last forever. I don't know why God does everything that he does, but I know him well enough to trust him on the things I find mysterious. He saw inside my heart, saw my rebellion, saw me bounding up the steps of the Tower two at a time, and loved me and rescued me anyway.

And so, unlike Alexandra Drennan, and Elohim, and the child programs, I look forward to the day not when sin first enters the world, but when it finally leaves. That's the true pinnacle Christians are longing for.

Talos was a figure in Greek myth, a mechanical guardian for the island of Crete. It seemed to qualify as a person, being able to think and speak, but when it lost its liquid metal blood, it died. This is an actual Greek myth. In TTP, a fictional philosopher called Straton of Stageira, a materialist in the philosophical sense, supposedly shot down the mystical musings of other philosophers by pointing out that no philosopher, no matter how clever, can survive without his blood. This is the Talos Principle. ↩︎

"Noema" is a Greek word, and not one I'd heard before, but according to Wikipedia its English usage is to mean "a figure of speech whereby something stated obscurely is nevertheless intended to be understood or worked out." Perhaps that's why the game doesn't define "noematics" for you. ↩︎

"Elohim" is actually plural. "El" means "god", but the Old Testament often uses "Elohim" to refer to God in particular, as opposed to any other supposed "god". ↩︎

This is a triumph of narrative delivery. Reading bits of documents, decoding ASCII, piecing together Elohim's thinking and getting a glimpse of what's going on behind the puzzles was as much fun as solving the puzzles themselves. But at the same time, people who just want to stick with the puzzles are free to. ↩︎

Edit: Part II is now here, although it didn't go in the direction I expected. ↩︎